Politics / November 5, 2025

Though he would eventually condemn Trump, the former vice president rejected transparency, the rule of law, and constitutional principles.

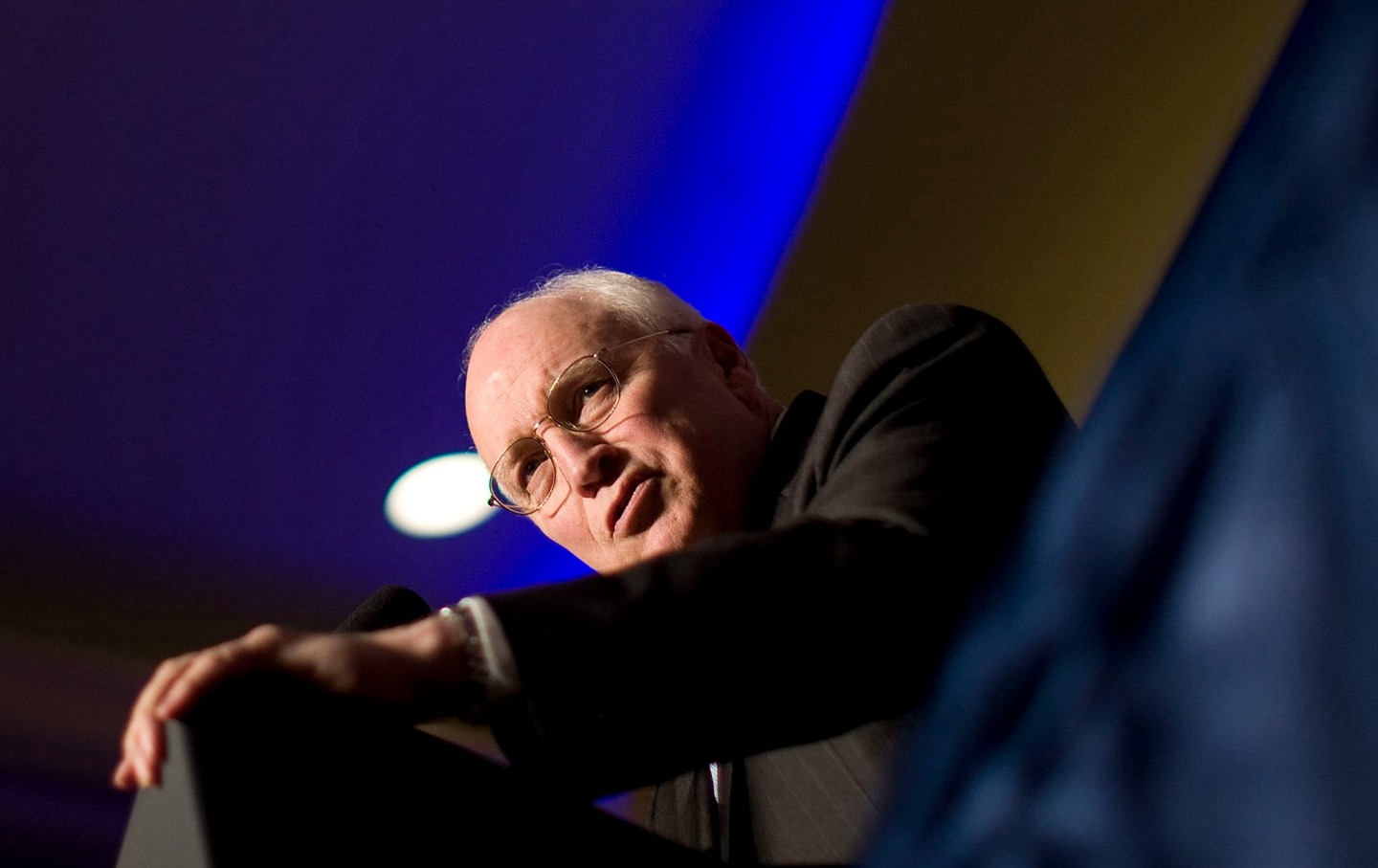

Vice President Dick Cheney speaks at the 35th annual Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington, DC, on Thursday, February 7, 2008.

(Chuck Kennedy / MCT / Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

Dick Cheney spent the last years of his long public life in open conflict with the Republican Party whose modern form he spent decades shaping. In a dramatic 2022 television ad that he recorded in support of his daughter Liz’s doomed congressional reelection bid as a lonely GOP critic of President Donald Trump, the former vice president, who died Monday at age 84, ripped into Trump as a dangerously irresponsible leader for the GOP that the Cheneys had once dominated.

“In our nation’s 246-year history, there has never been an individual who is a greater threat to our republic than Donald Trump,” declared the elder Cheney. The 46th vice president of the United States complained that the man who had been the 45th president and would become the 47th “tried to steal the last election using lies and violence to keep himself in power after the voters had rejected him. He is a coward. A real man wouldn’t lie to his supporters. He lost his election, and he lost big. I know it. He knows it, and deep down, I think most Republicans know.”

Perhaps there were Republicans who understood that Cheney was right. But they offered no evidence that they cared—and a good portion of the blame for that lay with Cheney himself. By 2022, the GOP had been acclimated to abuses of executive power not just by Trump but by Cheney and his associates during the years when the senior Republican manipulated world affairs as the most powerful—and secretive— vice president in American history.

Cheney’s unsuccessful attempt to pull his party back from the brink in 2022—along with his 2024 announcement that he’d vote for Democrat Kamala Harris—merely confirmed his marginalization by what had already become a fully Trumpian Republican Party—one that he had helped create.

Despite her father’s intervention, Liz Cheney was swept from office by Wyoming Republican primary voters who continued an evolution of the GOP that the elder Cheney had facilitated during the course of a half-century career characterized by the rejection of transparency, a refusal to respect the system of checks and balances and, ultimately, the creation of an super-empowered executive branch that was ripe for abuse.

Indeed, the arc of Cheney’s career offers a far more definitive measure of the GOP’s movement toward Trumpism than that of almost any other figure—save Trump himself.

Dick Cheney craved power. From the mid-1960s onward, he positioned himself as a behind-the-scenes but invariably influential player in successive Republican White Houses, a right-wing congressman who longed to be speaker of the House, a hawkish secretary of defense who became obsessed with regime change in Iraq, a corporate CEO who occupied the dark intersection of oil power and the military-industrial complex, and, finally and most damagingly, a vice president who used false pretexts, inflated claims about weapons of mass destruction, and manipulated “intelligence” to steer the United States into a catastrophic Middle East war.

Cheney was a résumé Republican. He claimed positions of enormous authority, yet he did so for a rogue’s gallery of Republican presidents whose scandals often anticipated those of Trump’s.

Cheney’s first White House boss was Richard Nixon, who had to resign as Congress began impeachment proceedings that grew out of his political wrongdoing, and dishonest and disreputable stewardship of the presidency.

Cheney served in Congress as a fierce ally of Ronald Reagan, who was investigated by Congress and the courts for presiding over an administration where key players arranged—and then lied about—a secret plan to violate the law by directing resources to its Iran-Contra coconspirators in the Middle East and Latin America.

Cheney headed the Pentagon in the White House of George Herbert Walker Bush, who pardoned Caspar Weinberger, Robert C. McFarlane, Elliott Abrams, and others who had been indicted, and in some cases convicted, by Iran-Contra prosecutors.

Cheney then left the public sector in pursuit of corporate power. His work in the 1990s with Halliburton—at a time when he briefly considered making his own presidential bid—was the subject of frequent controversy, as were the close alliances he maintained with the scandal-plagued executives of Enron, a firm that imploded amid accusations of institutionalized and systematic accounting fraud.

Cheney stepped back into the public service in 2001, as the prince regent to a boy president whose administration stands accused of “fixing” intelligence in order to convince Congress and the American people to support an unnecessary—and ultimately disastrous—invasion and occupation of Iraq. As part of that initiative, Cheney was repeatedly accused of promoting inaccurate claims about the supposed presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and an illusory “connection” between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda network.

Ultimately, Cheney found himself at the center of a multiyear investigation into how, on his watch as vice president, the Central Intelligence Agency employed tactics that the world understands as torture.

The 500-page summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report into the global torture regime that Cheney and his allies facilitated during the early years of the so-called War on Terror described a “brutal” and “flawed” program that was “in violation of US law, treaty obligations, and our values.” The report revealed evidence that Cheney and his allies had acted with stark disregard for basic premises of the American experiment—in particular, respect for the rule of law and for the system of checks and balances.

Arizona Senator John McCain said, in championing the release of the committee report, that the CIA interrogation program as it operated during Cheney’s time as vice president, “stained our national honor, did much harm, and little practical good.”

Yet, with Cheney taking the lead, key figures in the former administration rejected the standards for transparency and accountability that are essential to maintaining not just national honor but meaningful democracy. Back in 2009, when a newly retired Cheney was making unsubstantiated and irresponsible claims about so-called “torture memos,” US Senator Russ Feingold (D-WI) bluntly declared, “The former vice president is misleading the American people.”

And he kept doing so.

Refusing to face the facts—especially when they revealed the extent of his wrongdoing—Cheney decried the intelligence panel’s 2014 summary as “a bunch of hooey.”

He rejected what CNN described as “the central conclusion” of the study: “that CIA employees exceeded the guidelines set by Justice Department memos that authorized the use of ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ and that the agency misrepresented to Congress and the White House what it was doing.”

“The program was authorized. The agency did not want to proceed without authorization, and it was also reviewed legally by the Justice Department before they undertook the program,” claimed Cheney, choosing, as he did throughout his vice presidency, to dismiss actual information in favor of a personal narrative where he was always right.

Doubling down in defense of waterboarding and other abuses as “absolutely, totally justified,” Cheney announced that those who had engaged in tactics that have long been identified as torture “ought to be decorated, not criticized.”

Presumably, Cheney included himself on the longer list of those deserving decoration, as he announced, “If I had to do it over again, I would do it.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

The American Civil Liberties Union concluded, “Cheney has no regrets, even though the very policies that he wants his legacy to rest upon have been recognized as illegal and even criminal by the public and policymakers alike.”

It was this arrogance of power that consistently put Cheney at odds with American ideals and values regarding transparency and accountability. Even with the passage of time, even in the face of evidence that his own past statements had been wrong, the former vice president rejected any questioning of his absolute authority.

Cheney expected congressional Republicans—and conservative pundits—to embrace not merely his dismissal of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s majority report but his broader approach as well. And many did—just as they now defend Trump.

To his credit, Cheney recognized from 2022 onward that Donald Trump posed a “threat to our republic.” But that threat, with its frequent rejection of the rule of law and constitutional principles, was built on a foundation of past abuses—including, it must be acknowledged, those of Dick Cheney.

John Nichols

John Nichols is the executive editor of The Nation. He previously served as the magazine’s national affairs correspondent and Washington correspondent. Nichols has written, cowritten, or edited over a dozen books on topics ranging from histories of American socialism and the Democratic Party to analyses of US and global media systems. His latest, cowritten with Senator Bernie Sanders, is the New York Times bestseller It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism.