Feature / November 17, 2025

All too often, when parents can’t afford safe housing, the solution child welfare services offer is putting their children in foster care.

It was a Sunday this past June, and Virginia Ortega was heading to work at her job cleaning hotel rooms, putting in overtime so she could pay her rent. She asked her son Cesar (a pseudonym), an autistic 16-year-old who also suffers from hallucinations, if she should find someone to watch him while she worked, but he said no, he was old enough to stay home alone. When Ortega returned to her squat, triangle-roofed one-story house in southeastern Kansas City, Missouri, after work, the front door was hanging open and Cesar was nowhere to be found. Frantic, she asked her neighbors what had happened. One told her that the police had taken her son while she was at work.

Ortega, who is originally from Mexico and speaks Mixtec and Spanish, said a caseworker with Missouri’s child welfare agency eventually told her that her son was taken because she doesn’t have air conditioning. In Missouri, landlords are required to provide heat but not air conditioning, and her landlord has refused to get a unit for her. She doesn’t have the money to buy one herself. She told me that the caseworker told her, “No es seguro vivir conmigo”: that it’s not safe for her son to live with her.

Ortega had worked hard to make her house as safe as she could. Sitting on the tile floor of her small living room in September—her only furniture is a black love seat and a bare mattress on the floor of her bedroom—she told me that when she moved into the house, it was covered with rat feces. She got it as clean as possible, but the place still needed repairs: The kitchen cabinet doors were hanging off their hinges, and there was a large hole punched in the tile over her bathtub. Ortega tried to get her landlord to fix it up, but instead the landlord retaliated: She accused Ortega of using too much water and gas and then shut the water off. Ortega would like to move, but she can’t afford to put down a deposit on another home, and she doesn’t know how to apply for a housing voucher or for public housing. She has no family here in the United States to help.

When we spoke, months after Cesar was taken, Ortega still knew nothing about where he was or who was caring for him. “No sé nada,” she said, silently crying: I don’t know anything. She hadn’t been able to see him for three months, the longest they’d ever been apart. “Extraño mucho a mi hijo,” she said, holding her hands over her eyes: I miss my son very much. “Nomás puedo llorar”: All I can do is cry.

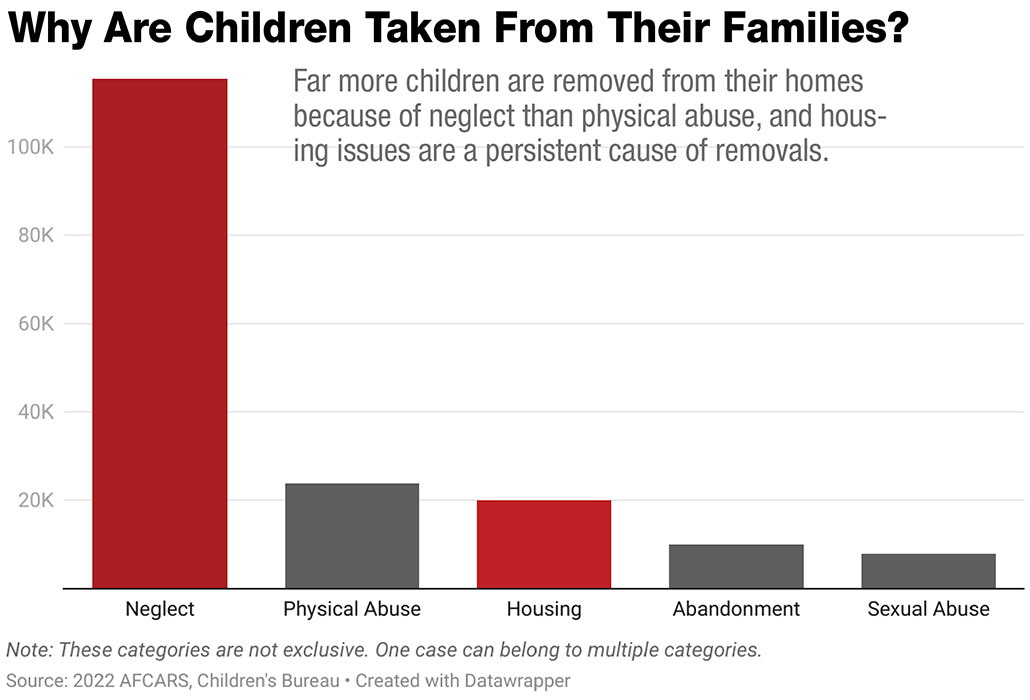

You might think that child welfare agencies remove children from their families primarily over suspicions of physical or sexual abuse. But the reality is that removals for the more nebulous category of “neglect”—which ranges from locking a child in a closet to leaving a child in the care of an older sibling so a parent can go to work—are far more common. In 2022, the most recent year for which federal data is available, neglect was the basis for 62 percent of removals in the country, which meant 115,473 children were taken from their families for this reason. In Missouri, neglect made up two-thirds of all referrals to a child welfare agency in 2024.

Most neglect cases stem from financial deprivation and its effects—such as inadequate food, clothing, or shelter. Research suggests that it’s poverty that drives these problems, not the parents’ unwillingness to address them. “There’s a substantial body of evidence that when you reduce poverty, there is less child-welfare-system involvement and less neglect in particular,” said William Schneider, an associate professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign with a focus on child welfare.

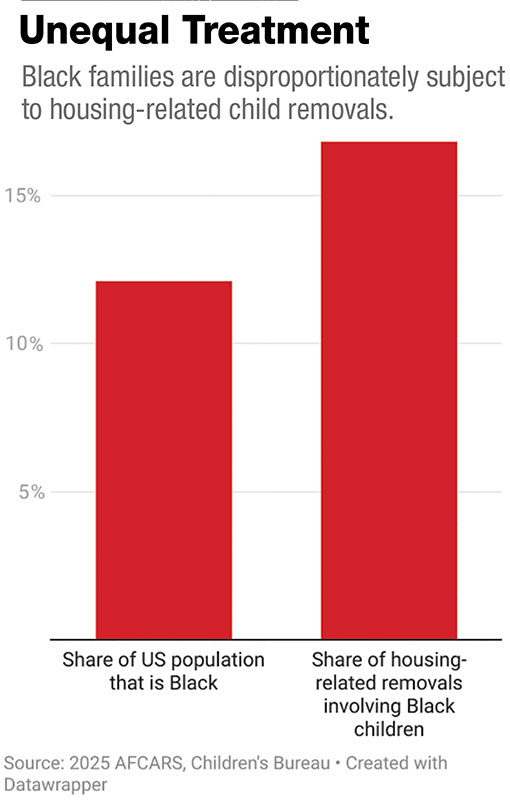

The inability to afford decent housing is a persistent driver of child neglect cases. Every year since 2015, inadequate or unsafe housing was cited as a reason for removal in about 10 percent of all cases in which children were taken from their families by child welfare agencies, even as the total number of children removed from their families has declined, according to federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data. In 2023, the most recent year for which data has been released, nearly 16,000 children who were removed from their homes, representing 9 percent of all removals, were deemed to live in substandard housing. Those children may have been removed for a combination of factors that could also include a parent’s substance abuse or mental illness, but some children are removed solely because their families’ housing is inadequate. In 2021, the most recent year for which there is data, at least 1,467 children were taken from their families because of housing issues alone. This phenomenon disproportionately affects Black families; on average between 2013 and 2021, nearly 20 percent of children removed because of housing were Black, even though Black people make up about 12 percent of the population.

Those numbers are most likely an undercount because of variations in how caseworkers in different jurisdictions fill out paperwork. Even so, some states are clearly hot spots for housing-related removals. Missouri is one of them, as are states as diverse as Georgia, Maine, Michigan, and New Mexico. In Missouri, between 2013 and 2021, an average of 18 percent of children per year who were removed from their families were removed at least in part because of their housing. In 2019, before the number of removals fell during the pandemic, the state removed 138 children from their families solely for this reason. Black children in Missouri are also disproportionately affected: On average, they accounted for 14 percent of removals in the same period, even though Black people make up 11 percent of the state’s population.

In Missouri, a substandard apartment is reason enough for judges to agree to removals, said Kathleen Dubois, a retired family court attorney in St. Louis. “Nobody blames the landlord,” she told me. “They just take away the kids.” Kathy Connors, the executive director of the St. Louis homeless shelter Gateway180, sees the same thing: There are an “awful lot” of instances in which mothers living in her shelter have their children taken away if they can’t find permanent housing fast enough.

The stakes are incredibly high. “Separating a parent and a child causes trauma however it comes about,” said Josh Gupta-Kagan, a Columbia Law School professor who specializes in child neglect and abuse law. One study in Sweden found that children removed from their families are much more likely to be hospitalized for mental illness and to commit suicide. When children are taken from their families, even if they’re placed in a caring foster home, “you rip them from their school, you rip them from their community, their friends, and you erode kinship relationships,” said Clark Peters, an associate professor at the University of Missouri with a focus on child welfare.

Meanwhile, any removal starts a relatively short clock: If parents fail to reunify with their children before 15 months elapse, child welfare agencies must move to terminate parental rights. That’s when families risk losing their children forever.

The head of Missouri’s Children’s Division, Sara Smith, insists that caseworkers in her agency use an individualized approach in determining when a removal is necessary. “In and of itself, we wouldn’t take homelessness as a report,” Smith asserted. “We would be looking at if the child’s basic needs are met, if the family does have some kind of housing.” In addition, she said, an abuse or neglect report is not the only option available; caseworkers can make a “preventative service referral,” which points families to community organizations—nonprofits, churches—that might be able to provide resources. Families can also choose to do a “temporary alternative placement agreement,” or TAPA, a voluntary process outside the court system that places children with other family members. But Smith acknowledges that the division doesn’t spend its own funds on securing or fixing housing for families. “Children’s Division in and of itself doesn’t provide…some of the things that are needed for housing situations,” she said. “We really do rely on our community partners.”

Missouri operates a statewide hotline for initial reports of child abuse and neglect. When hotline staff receive a report, they are prompted to note “conditions or content of the household which are unsafe or unsanitary,” as well as whether the utilities are turned off and if there is a “lack of shelter.” A report is referred to a local child welfare department in the state when “lack of heat or shelter, or unsanitary household conditions are hazardous and could lead to injury or illness of the child(ren) if not resolved.”

Once a report is funneled to a local department, a caseworker completes risk and safety assessments. A point gets added to a family’s risk score if “current housing is physically unsafe,” while homelessness adds two points. One of the factors included in the safety assessment is whether “the physical living conditions are hazardous and immediately threatening to the child’s health and/or safety.” This could include “situations where significant structural dangers exist in home (e.g., leaking gas from stove or heating unit, lack of water or utilities, exposed and accessible electrical wires),” as well as things like “repeated insect and rodent bites” and “ongoing presence of animal feces.” If one or more safety threats are present, and an intervention plan or TAPA is deemed insufficient, then the assessment states that children must be removed. (Smith noted that the risk assessment, which is 20 years old, is currently being redeveloped.)

While the risk and safety assessments are guides, a lot comes down to a caseworker’s instincts. “Doing this work for a while, you know when you go into a home where you cannot fix,” Smith said.

Darrell Missey became the director of Missouri’s Children’s Division in 2022. A former judge who heard child welfare cases, he took the job with the goal of reducing removals. “I was trying to get people to give folks the opportunity to come up with answers besides separating the family,” Missey said. Still, he often felt forced to remove children because he didn’t have any housing to offer their families. Missey left the position in late 2024. Smith, his replacement, reassigned the person Missey had hired to work on removal prevention to a different role and fired his deputy director, he said. There is a “mentality” that “pervades the state” of removing a child instead of finding a way to fix or find housing, he added: “Missouri’s leadership is not interested in preventing children from coming into foster care.”

A unique aspect of Missouri’s child welfare system makes removals even more likely. Once the Children’s Division determines that a child should be removed, caseworkers hand the case over to a juvenile officer, who has the sole purview of deciding whether to seek removals or reunifications. The officers are hired, supervised, and fired by the very judges that they petition to remove children, meaning there’s “no separation of powers,” Missey said. And while the federal government requires state agencies to make efforts to prevent removals and reunify children with their parents, juvenile officers aren’t subject to those rules.

Some states have laws that say, at least on paper, that children should not be removed from their families because their parents can’t afford decent housing. About half of states exempt parents’ financial inability to provide things like shelter for their children from the definition of child maltreatment. At least three states have statues saying homelessness does not constitute neglect.

Missouri does not. While it has exceptions in its maltreatment statutes for corporal punishment and refusing medical care on religious grounds, it has none for poverty or homelessness. And while removals are supposed to occur only when a child is at imminent risk of harm, caseworkers often consider housing issues indications of that risk.

That’s what happened to Lauren, whom I met at family court in Kansas City. Her son John (both pseudonyms to protect the family’s privacy while their case is pending), now 9 years old, was born with chronic kidney disease. Through tears, Lauren recalled that, a few years ago, both her mother and John were hospitalized at the same time. Trying to care for both of them, Lauren lost her job as a data entry clerk. When it came time to renew the lease on her home in Kansas City, she declined, believing she would soon move in with her mother. Then her mother died. Lauren and John were evicted, and they eventually moved into an extended-stay hotel.

The hotel wasn’t perfect, but it worked for them: They lived in a suite with a refrigerator, a stove top, and a table and chairs. “That was like our home,” Lauren said. She had food in the refrigerator, and she placed the new clothes she had bought for John on hangers. “We were sleeping good every night. He was eating, taking baths.” John was transported from the hotel to school and back. The other long-term residents of the hotel became their community. Between John’s Social Security disability payments and Lauren’s income driving for DoorDash, she could cover her costs.

Still, John’s doctor repeatedly told her that she needed to move to permanent housing, but the hospital social workers didn’t offer much help. They gave her a piece of paper listing resources she could contact—all of which she had already tried.

And Lauren still couldn’t get a full-time job. John’s dialysis took place three days a week, four and a half hours at a time; he had other medical appointments and hospitalizations, too. “I spend more of my time at this hospital than I can do at a job,” Lauren said. But she’d developed a plan: She had decided to move in with an elderly cousin who lives alone in a three-bedroom house in Oklahoma City and has a spare car. In Oklahoma, Lauren heard, she could get off the waiting list for a Section 8 rental voucher in a matter of months and finally get her own housing. She had packed up and was even approved for Medicaid and food stamps there. All she was waiting for was the hospital to send her son’s records over to a new dialysis center near her cousin. She planned to move before Labor Day.

Instead, a hospital employee called the state hotline to report her to the Children’s Division. The paperwork outlining the reasons for her son’s removal notes that they had stayed in the hotel for over a year. That presented an imminent risk, according to the division, because John had been removed from the kidney donor list when it was discovered that Lauren didn’t have permanent housing, even though the wait for a transplant typically lasts years. The hospital also claimed that John wasn’t taking his medications and that he was missing his appointments—a claim that Lauren vehemently denies. Even when she briefly didn’t have a car, they never missed appointments, she said, showing up late only when the medical transport was late.

Lauren’s son is now living with her eldest daughter. Even though he’s with a family member, the experience has been traumatic. For the first week, Lauren couldn’t see or talk to him. “They treated me like I was an abusive mother,” she said. The two had never spent that long apart. John cried every day and began losing weight. Eventually, Lauren was permitted 10-minute phone conversations with him. “He cried and cried—he cried when he got on the phone with me, he cried when they made him get off,” she said. Lauren herself couldn’t sleep or eat. “I was just sitting up waiting for the next call.”

When we met in September, she was allowed to see him, but only for an hour while he was at dialysis, and only when someone at the Children’s Division was available to supervise the visit. John cried every time she left. “He’s really not himself,” Lauren said. “I can just see in his face he’s not happy.” He’s asked her if this all means she’s not his mother anymore and insists he doesn’t want a new mom. “I’m all he got. I’m all he knows,” she said.

Lauren has been told she has to have permanent housing to be reunited with John, and she’s trying, but “it’s hard,” she said. She’s still on the waiting list for Section 8 and public housing. “I just don’t see how they can get away with doing this to people,” she said tearfully, heavy bags under her eyes. “I still take good care of him, and I feel like that should be all that matters.”

Once they have lost custody of a child, families can be held to an even higher standard before they can reunite. Any state-level protections against removals due to poverty or homelessness disappear when it comes to whether and when children can go home. Caseworkers and judges have far more discretion to tell parents what they must accomplish before they can get their kids back.

Ortega is dealing with these hurdles now. To get her son back, a judge told her, she had to have decent housing, a job, and $3,000 in a bank account, she told me. But after Cesar was removed, she was fired—someone at work had spread a rumor that she’s a bad mother. Ortega suffers from leukemia, which makes it hard for her to find another job. The court order removing Cesar said she had been referred to affordable-housing programs, but Ortega couldn’t make use of that referral. She can’t read; her mother didn’t send her to school.

To make matters even worse, she no longer gets the $960 a month that Cesar receives in Social Security disability benefits. When she went to collect the checks, she was told that they are going instead to whoever is caring for Cesar. When we met, she was on the verge of losing her housing without any income.

“No le hice nada a mi niño,” she said: I never did anything to hurt my son. But that’s not enough in the court’s eyes. “Si no tengo trabajo, no me pueden entregar a mi hijo,” she said: If I don’t have work, they can’t bring back my son. “Si no tengo casa mejor, no me lo van a entregar a mi”: If I don’t have a better house, they’re not going to bring him back to me.

Whether or not a child was originally removed because of problems with housing, child welfare agencies often insist that a family secure or improve their housing situation before reunification. In Missouri, the standards are “really strong” about what qualifies as an appropriate home, Dubois said, and they exclude brothers and sisters sharing rooms or parents sharing bedrooms with their children. Living at the Gateway180 shelter is typically not considered adequate housing to allow parents to get their children back, Connors said. She has seen many families who come to the shelter working to reunify with their children. But since she began working there in 2016, she has seen only four successful reunifications. “It does seem like it’s a situation where the goalpost keeps getting moved further and further,” she said. Three studies conducted since 1996 have concluded that 30 percent of children nationally could have been reunited with their families immediately if the families had adequate housing.

The affordable-housing crisis makes this an even more difficult barrier to overcome. Housing costs for both renters and owners rose faster than inflation last year, with nearly half of renters spending more than a third of their income on rent. The median rent jumped 4.1 percent. Homelessness reached the highest level ever recorded.

A long history of housing discrimination in the United States may explain, at least in part, the disproportionate impact of housing-related removals on Black families, with Missouri being no exception. Both Kansas City and St. Louis, the state’s largest cities, developed redlining maps that banks used to deny loans in “undesirable” areas. In the 1920s, Kansas City developers adopted racial exclusion policies that prohibited sales or rentals to Black people. St. Louis had an ordinance prohibiting Black people from moving into houses on predominantly white blocks. This legacy is still visible today. The dividing line in the city is Delmar Boulevard: The area north of it is full of vacant and run-down buildings; immediately south of it, brand-new housing and gym complexes spring up.

The cheaper housing north of Delmar is typically very old and in need of significant repairs. “The landlords are really notorious,” Dubois said. They also frequently resort to evictions. Family court attorney Laurie Snell said the same thing of Kansas City. “There are a lot of slumlords,” she told me.

Sometimes all that families need to remain stably housed and prevent a child’s removal is some extra money. But while the Children’s Division doesn’t use its funds to help these families with housing, the agency does directly fund the housing needs of foster families, as federal law requires. In Missouri, licensed foster-care families receive between $509 and $712 a month for a child, depending on the child’s age, to cover housing and other basic needs, plus an additional $91 a month for children 3 years and younger to cover things like formula and diapers. They receive between $320 and $700 a year for clothing, as well as monthly payments of as much as $2,034 for children with “elevated needs.”

That kind of money would have been a godsend for A.M. and her husband, E.M. (they requested anonymity out of fear that speaking out would bring them back to the attention of the Children’s Division), who have four children, three of whom have intellectual or mental disabilities. A.M. and E.M. lost the custody of some or all of their children multiple times over the past three decades. The first time their family became entangled in the child welfare system was in 1990, when A.M.’s mother called the state hotline to report them. After showing up at their St. Louis apartment, a caseworker offered them cleaning supplies without removing their son (then their only child). But five years later, after A.M. was “hotlined” again, the caseworker who visited their home deemed it too dirty, and their son was removed. “It was heart-wrenching,” A.M. recalled. She suffers from depression as well as physical disabilities, but no allowance was made for any of her conditions. She and E.M. had to get the house clean and ensure that the utilities were kept on, plus attend parenting classes, to get their son back. It wasn’t easy; E.M. kept having to take time off work to meet the requirements, and he worried that he’d lose his job.

The last time their family was separated, after her children’s school district called the hotline, it took A.M. and E.M. a year and a half to get back their youngest son, who is autistic. He receives Social Security disability payments, but while he was out of their home, A.M. and E.M. not only didn’t receive those checks but were made to pay about $200 a month in child support to the state. A.M. was still struggling to get on disability benefits herself; E.M. was putting in 14-hour days at work. “We almost lost our home,” A.M. said. Once they were reunited with their son, they got most of his Social Security money back, but it all went to their landlord to catch up on rent.

Memories of the removals still bring A.M. to tears. “It seemed like it happened every five years,” she said. “All of it was because of the house.” Every time the children were taken, the foster families received monthly checks to care for them. If those payments had instead gone to A.M. and E.M., it “would have meant a lot,” A.M. said. “Being able to pay our bills, actually get the stuff the kids wanted.”

“Here in Missouri, they look for any and every excuse to take the kid away,” E.M. added. “I think the state would have saved a lot of money by helping the biological parents get through whatever issues there was.”

Indeed, research has found that when families get help with housing, their involvement with child welfare agencies decreases. During the pandemic, eviction moratoriums significantly drove down reports of child neglect. An in-depth study by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development found that families who received housing vouchers had children removed far less often than those who didn’t. Another HUD demonstration project found that families who were given supportive housing ended up getting their children back at twice the rate of families who weren’t.

But most child welfare agencies don’t offer such interventions. One big reason is that the federal government reimburses states for money they spend supporting foster parents through Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, which is the main source of child welfare funding. But it won’t reimburse state spending to directly support birth families. Ruth White, the executive director of the National Center for Housing & Child Welfare, argues that agencies have other flexible funding they could use this way, including other Social Security Act money, funds from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, and state and local money. But agencies and the array of nonprofits that work with them “are first and foremost concerned with funding the apparatus,” the child welfare system itself, White said.

“We don’t have an entitlement to shelter,” she added. “We have an entitlement to foster care.”

Caseworkers, meanwhile, don’t typically focus on helping families with housing. Smith, the Missouri Children’s Division head, said she’s trying to cultivate a culture of “not just giving families a stack of papers” to point them toward outside resources but giving them “a warm handoff.” But as Ortega’s and Lauren’s experiences show, caseworkers still usually just hand out papers. Nationally, caseworkers are “already overloaded—it’s an incredibly stressful job,” Schneider, the child welfare scholar, said. The median caseworker handles 55 cases a year. The turnover in Missouri’s Children’s Division was 28 percent in fiscal year 2025. Even if all a family needs, as in Ortega’s case, is an air conditioner, caseworkers may not have the funds—and might resist calling around to find an organization that does.

Caseworkers may also feel that this kind of work isn’t in their job description. They “have been trained to think about promoting individual responsibility,” Schneider said. Dubois, the retired family court attorney, said that many caseworkers feel they shouldn’t “enable people” by helping them: “‘If [clients] are unable to handle things, we’re not going to do it for them.’”

The problem is poised to get even worse in Missouri. Several of the people I spoke with saw Smith as being in favor of increasing the number of removals. That’s become particularly clear in the wake of the death of Grayson O’Connor, a 5-year-old who fell from the window of an apartment building in late 2023, after the Children’s Division had received multiple calls about him. The division has “work to do throughout the state on these types of cases,” Smith told the local ABC affiliate in response. In August, despite telling me that most housing-related reports are handled through temporary alternative placements, Smith sent a memo to all Children’s Division employees saying that they are obligated to consider whether the “imminent danger” is low enough for a temporary alternative placement or the situation is too complex to make use of one. In that case, the memo instructs, staff must immediately make a request to remove the child. Immediately afterward, filings for abuse and neglect shot up from an average of 33 a month between January and July to 95 in August.

“It’s bad,” said Snell, the family court attorney, and “it’s not getting better.”

Bryce Covert

Bryce Covert is a contributing writer at The Nation and was a 2023 Reporter in Residence at Omidyar Network.